The device collects particles from the air as liquid droplets. It helps find viruses, bacteria, and pollution for health checks.

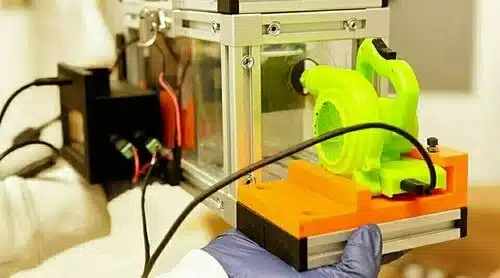

Airborne hazardous chemicals are usually present in low concentrations, spread easily, and are hard to trap—yet detecting them is critical for protecting health and the environment. A new four-by-eight-inch device called ABLE, developed by researchers at the University of Notre Dame, with collaborators from the University of Chicago, addresses this challenge. ABLE can already be useful in places like hospitals, where it detects airborne viruses, bacteria, and nanoplastics directly from the air. This could reduce the need for invasive tests like blood draws, especially for vulnerable patients such as newborns in intensive care.

Usually, testing airborne biomarkers as gases needs large, costly machines like mass spectrometers. But turning these samples into liquids allows the use of simpler, more accessible tools—such as paper test strips, enzyme assays, electrochemical sensors, and optical devices.

The ABLE device pulls in air, adds water vapor, and cools it so water droplets form on a surface covered with tiny silicon spikes. These droplets gather airborne contaminants and slide into a reservoir, where they can be tested for biomarkers.

Costing less than $200 to make, ABLE provides an affordable option for both clinical and environmental monitoring. Ma’s lab, the Interfacial Thermofluids Lab (ITL), is working to shrink the device further so it can fit into portable systems or robots for real-time sensing. They are also partnering with healthcare providers to help monitor the health of newborns in critical care.

“Many important biomarkers – molecules your body produces when it’s dealing with pathogens – are very dilute in the air. They could be at the parts per billion level. Trying to find them is like locating six to seven people in the global population – very difficult,” said Ma, the study’s first author, who conducted the research as a postdoc at the University of Chicago.